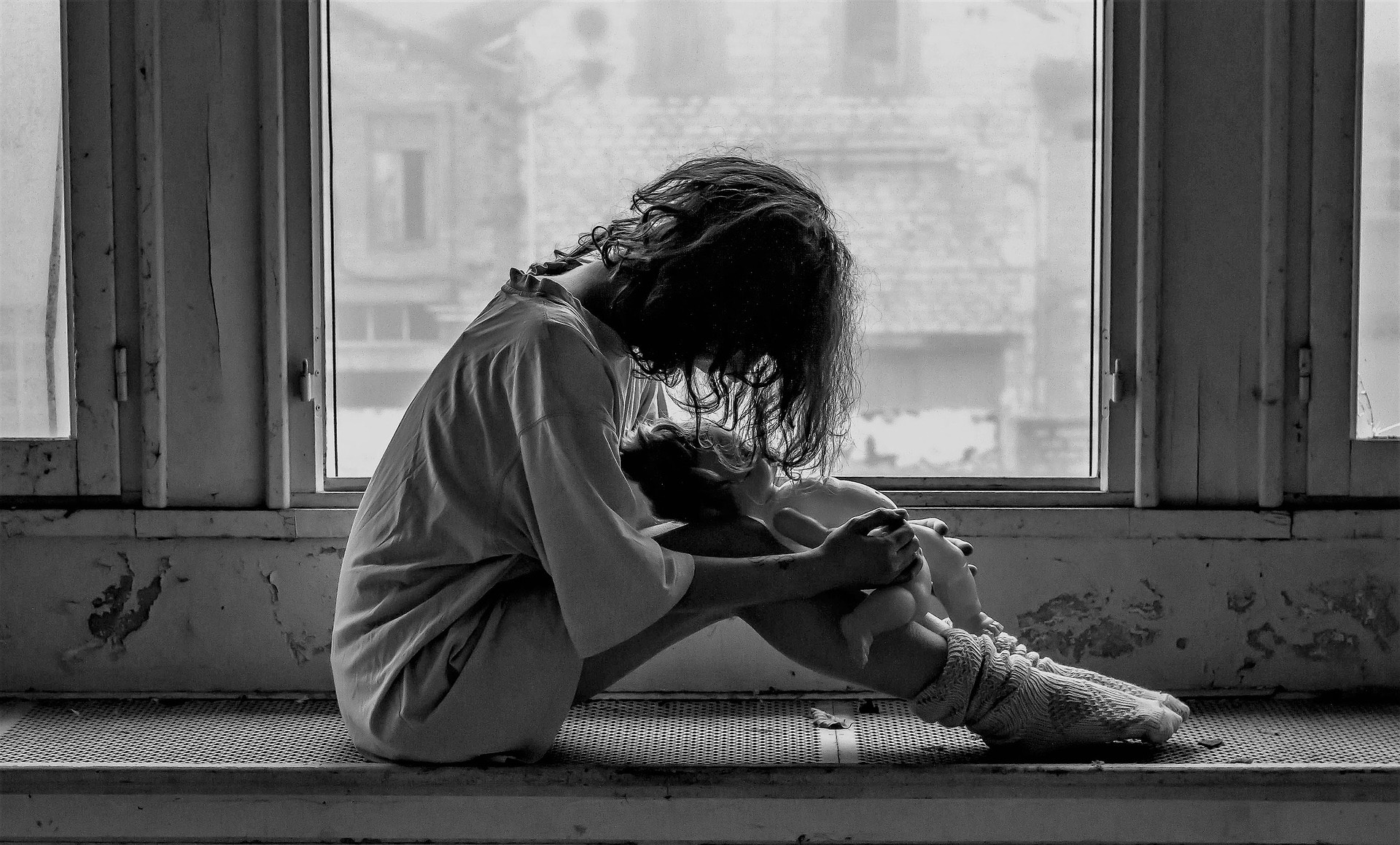

When I thought of a co-dependent relationship I used to think of it as warm and caring relationship, where the couple are so in sync with each other’s needs and behaviours that the relationship just flows naturally and effortlessly from one moment to the next. Apparently, this is not the case.

The oxford dictionary defines co-dependency as ‘Excessive emotional or psychological reliance on a partner, typically one who requires support on account of an illness or addiction.’

When my therapist introduced the term in one of our sessions, I was confused – I’m not co-dependent, I see myself as a totally independent woman, I’m not even in a relationship. The term ‘co-dependency’ was initially introduced in the mid-1980s and at that time it was used primarily to describe the behavioural patterns of spouses or partners of persons who were suffering from substance abuse problems. Since then research into family dynamics and dysfunctional families has broadened the definition of the co-dependent individual. Co-dependent is now the term given to any person raised within a dysfunctional family unit who is emotionally dependent on an outside source to boost their self-esteem.

I still wasn’t buying that. I don’t need to feel needed, I’m not a people pleaser. But these labels often put us off from looking deeper into ourselves and looking at where these behaviours actually come from. We immediately get defensive and shut down, as I did in my therapy session, when we initially started talking about it. It wasn’t until we started talking about my upbringing that things started falling into place.

I still wasn’t buying that. I don’t need to feel needed, I’m not a people pleaser. But these labels often put us off from looking deeper into ourselves and looking at where these behaviours actually come from. We immediately get defensive and shut down, as I did in my therapy session, when we initially started talking about it. It wasn’t until we started talking about my upbringing that things started falling into place.

Co-dependent individuals have certain characteristics that define them, so even if consciously you are the most independent person you know, subconsciously there are defence mechanisms in the form of co-dependent behaviours that are protecting you from feeling your pain.

As we talked my therapist outlined certain behaviours that are common in co-dependent individuals:

- They cannot say ‘no’ and tend to let others walk over them.

- They are the parents who cannot let go and allow their children to grow up; the over-supportive wife, or a loyal worker who is forever working extra hours without pay because they feel that the gratitude of their employers makes it worthwhile.

- They always put others first and often at their own expense.

- Co-dependents are compulsive in everything they do. They can rush headlong into relationships which can be painful, often short-lived and ultimately are destructive in one form or another.

- Co-dependents are quite often compulsive workaholics, drinkers, hobbyists or over-achievers.

- Co-dependents are the ‘adult’ child who has been brought up in a family system which was dysfunctional and who, in consequence, suffers from emotional wounds that have never had the opportunity to heal.

When put in front of me, alarm bells started ringing; over loyal employee who works extra hours for nothing, check. Someone who cannot say no without feeling guilty, check. Putting almost everyone before themselves, check. Compulsive workaholic, check. Compulsive over-achiever, check (although I did stop and think about this one, I’m really proud of how hard I work and what I have achieved.) But the one that got me most was the ‘adult’ child. I’m the eldest of three siblings, and my parents have constantly pushed me into the ‘adult’ role. I have felt responsible for my siblings from as far back as I can remember. I have been a ‘friend’ to my mother since secondary school, with her confiding in me how unhappy she is with my father (they are still together). I have been my father’s sounding board, where he rattles off his opinions at me about everything under the sun, and dismisses anything I have to say. Consequently my teenage years and my early twenties were spent believing everything he says on all matters, which did wonders for his self-esteem, but very little for mine.

It seems that co-dependence is a direct result of being raised in dysfunctional family. Now that is very subjective, many of my friends said their families were dysfunctional, however when I spent time around theirs, it wasn’t dysfunction, it was disorganised and I yearned for that kind of disorganisation. At home, things were never disorganised. I was told what to wear, what to do, what to eat, what to think.

It seems that co-dependence is a direct result of being raised in dysfunctional family. Now that is very subjective, many of my friends said their families were dysfunctional, however when I spent time around theirs, it wasn’t dysfunction, it was disorganised and I yearned for that kind of disorganisation. At home, things were never disorganised. I was told what to wear, what to do, what to eat, what to think.

Dysfunctional families have a set of rules that everyone has to follow. Ours were:

- That we could never have friends around.

- That we could never talk about what was happening at home, to anyone, including friends.

- That we had to pretend that we were one big happy family, whenever we went to social events.

- That we could never talk about my dad’s affair, or his temper, or my mum’s affair, or how fear was used to control me and my siblings.

In homes where co-dependency is bred, everything is kept behind a wall of denial. The problem does not exist, and help is not needed, sought or accepted.

The three rules regarding this ‘denial belief’ are:

- Deny that anything is wrong.

- Deny that the children have anything other than a loving and nurturing home.

- Deny that the parents are anything less than perfect.

Growing up in that denial, I pretended everything was fine at home. Even my best friend didn’t know what was happening. It wasn’t until years later that I started confiding in her how life was at home, did she realise why I used to act the way I did.

Children from such a background are always on their guard, never learning to relax and be themselves. It was like that for me, I didn’t know who I was until my late twenties when I started learning about myself. Even when I started learning about myself, it was years later until I had the confidence to express myself. I was so used to hiding how I felt, that I never really asserted myself. I was so used to doing what my parents expected of me, I never said no to anyone. The only praise I got from my father was when I achieved, so here I am 4 degrees later with my self-esteem linked to achievement and what others think of me, denying to my therapist that I’m a co-dependent woman.

Leave a Reply